Market Strolls, Mythical Dragons, and Moments That Moved Me

My Final Stop: Krakow

Dz and I took a night bus from Prague to Krakow to save money on accommodation, which was both our smartest and worst idea. The bus was cramped, sticky, and impossible to sleep on. But who needs sleep when you’re in EUROPE?!!

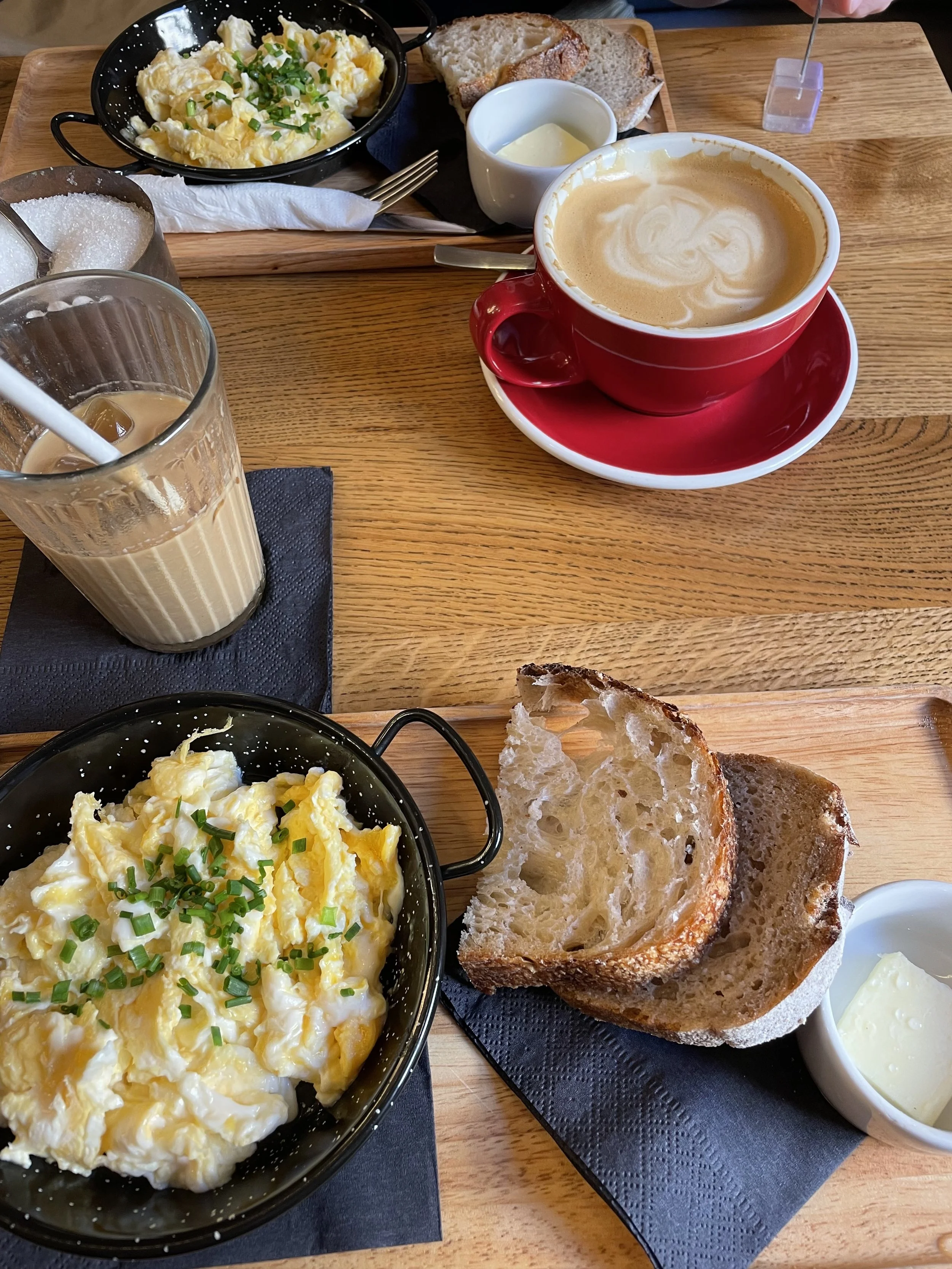

We arrived in Krakow at… 5 AM? 6 AM? Who knows—it was all a blur. Since our hostel didn’t open until 9 AM and breakfast spots didn’t open until 7, we had some serious time to kill. We wandered around aimlessly until we finally found somewhere to eat, then dragged ourselves to Dizzy Daisy, our hostel, to check in.

From the outside, it looked like a boring, featureless building, but inside? Massive rooms, high ceilings with intricate moldings, and these amazing detailed wood doors. One thing about European hostels—they always surprise you. I would never expect these buildings to look like they do from the outside! It's always my favorite part walking up feeling unsure and then going in and realizing the beauty of the space.

Our room was a 12-person mixed dorm, which was a first for us, and for some reason, Dz and I weren’t even sharing a bunk. While unpacking, a man walked into the room. He was… interesting. Older—like, 70s—dressed in some kind of hippie-chic attire, and he carried himself like he owned the place. Dz and I exchanged looks because, let’s be real, we’d never seen someone that age in a hostel, let alone in a 12-person dorm. On a top bunk.

Naturally, I introduced myself, because how else was I supposed to get his story?

Turns out, he was born and raised in Krakow but absolutely hated it—so much so that he moved to Costa Rica and now travels full-time as an artist, selling paintings across the world. And when it comes to accommodations? He doesn’t pay for them. Instead, he has a girlfriend in every city he visits so he always has a place to stay. (Except this time, he and his Krakow girlfriend had broken up, so… top bunk it was.)

Every day, he’d ask us what our plans were and then scoff when we told him. "Why would you come here?" He was genuinely confused about why anyone would visit Krakow.

Mornings in the Hostel = Pure Horror

At about 6:30 AM, I woke up to a weird bouncing sound. Now, in a hostel, any strange sound is alarming. Half-asleep and glasses-less, I tried to figure out where it was coming from. And then, across the room, I saw it—legs. Straight up in the air.

I scrambled for my glasses, and sure enough, it was our 71-year-old roommate. Doing bicycle exercises. On the top bunk.

After his morning warm-up, he spent 10 minutes with his legs up against the wall—for blood circulation, apparently. I had never seen anything like this in a hostel before. Ever. Naturally, I asked him about it (because, again, we’re friends now), and he casually responded,

"Yeah, that’s why I need the top bunk—so I can do my exercises."

Hmm. Okay.

Day One: Exploring Krakow

Our first day was all about sightseeing. We wandered through Main Square, which is absolutely stunning. The layout felt like a maze—every time we walked in a different direction, we found something new. The square itself is huge, lined with beautiful but understated buildings, symmetrical and elegant without being over-the-top.

Right in the center is Sukiennice, Krakow’s old international trade hub. We also stopped at St. Andrew’s Church and visited Wawel Cathedral, which was breathtaking. Somewhere along the way, we became obsessed with these jelly-filled doughnuts and ate at least two a day for the rest of the trip.

For dinner, we found a small spot that I wish I could remember the name of because the pierogies were life-changing. We ordered a mix of everything—potato and cheese, mushroom, meat-filled—and even tried dessert pierogies, which I hadn’t even heard of before but instantly loved.

Day Two: The Wawel Dragon

The next morning, we headed back up to Wawel Castle, curious about a dragon legend we’d heard about. The story goes:

"Long ago, a dragon terrorized the people of Krakow, demanding cattle as ransom (or, according to some, virgins). No knight could defeat it—until a young shoemaker named Skuba stuffed a ram’s hide with sulfur and pitch. The dragon ate it, became unbearably thirsty, and drank so much water from the Vistula River that it exploded. The people rejoiced, and to this day, a statue of the dragon stands by the river, breathing fire every hour."

So obviously, we had to see the Dragon’s Den for ourselves. Walking through, I was terrified—it was cold, dark, and echoed in a way that made it feel like a dragon could jump out at any second. I stuck close to Dz, you know, in case she needed to slay it for me. At the end of the cave stood the fire-breathing statue, which honestly was a little life-like but very cool.

Learning Krakow’s History

In the afternoon, we joined a walking tour of Krakow’s old Jewish quarter and former ghetto, since we’d be visiting Auschwitz the next day and wanted to understand more of the history beforehand.

The tour was only $5, and I highly recommend doing these kinds of “free” or budget walking tours in any city. The guides are usually locals who give personal insights you won’t find in a textbook. We learned about how quickly everything changed in Poland, how confusion and fear spread overnight, and how brave individuals—doctors, business owners—risked everything to help.

By the end of the tour, we felt heavy but grateful—to be able to learn, to listen, and to carry these stories forward.

To lift our spirits, we stopped by a food market on the way back. Dz tried zapiekanka (basically a long baguette with cheese, mushrooms, onion, ketchup, and sometimes meat), while I, of course, got more pierogies.

And yes, I have some Polish heritage, so I’ve had pierogies my whole life. But having real Polish pierogies in Poland? That’s a core memory right there. If I could’ve shipped them home, I would have.

Back at the hostel, our 71-year-old friend was waiting. We told him about everything we’d learned that day, and, unsurprisingly, he judged us.

"Why would you want to learn about that?" he asked, genuinely puzzled by our interest in history. But after a moment, he added, "It’s nice that young people still care."

Day Three: Visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau

We knew this would be a heavy day—probably the heaviest of the entire trip—but we also knew how important it is to learn and see first hand. As difficult as it would be, we felt a responsibility to bear witness, to hear the stories, and to see the places where these atrocities occurred. Because if we don’t, there’s a risk that history could repeat itself.

Visiting Auschwitz was something we decided to do when planning our time in Poland. I’ve had an interest in learning about the Holocaust since high school, and over the years, I’ve read books, watched documentaries, and studied films about World War II and the Holocaust. But nothing—absolutely nothing—could have prepared me for what it felt like to actually stand there.

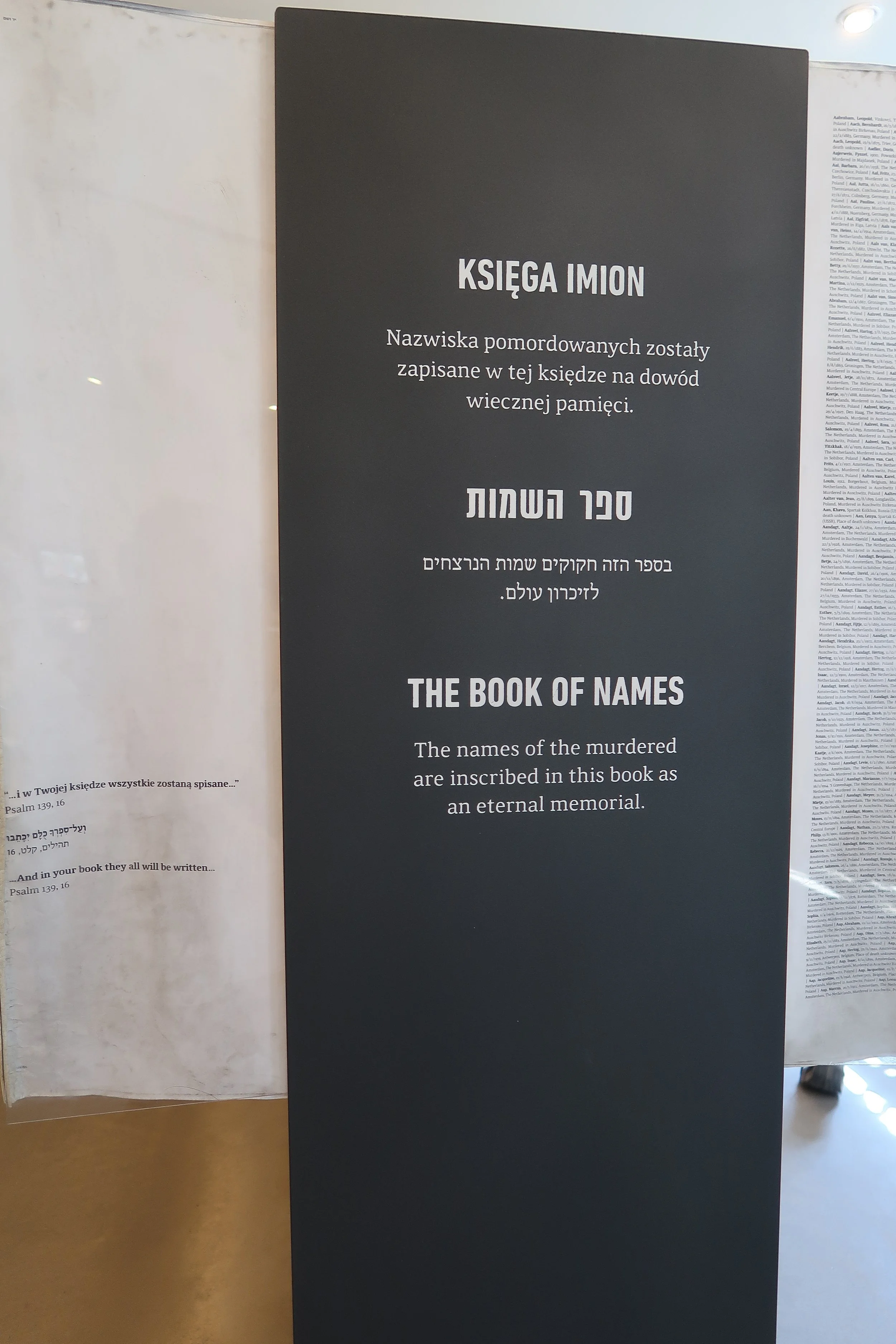

From the moment we entered, it felt like time slowed down. As we walked into the camp, an audio played softly, reading the names of prisoners—one after another—like a steady drumbeat that echoed in time with our steps. It was haunting.

When we reached the front gate and I saw the words "Arbeit Macht Frei"—"Work sets you free"—my heart sank. I’d seen that phrase countless times in photos and films, but standing in front of it in real life brought an entirely different weight. Everything I had read, watched, and learned about the Holocaust felt suddenly closer—no longer distant stories, but something I was now standing in the middle of. The reality of what had happened here was overwhelming.

Inside, the tour began. We walked past the spot where the camp’s orchestra once played every morning and evening as prisoners were forced to march to and from labor. The idea that music was used to keep them in time—and to calm new arrivals stepping into the camp for the first time—felt so twisted.

I want to be honest here: I don’t feel right giving a play-by-play of the tour. It doesn’t feel appropriate to list every stop or describe each building. Writing about this is already difficult—not because I regret visiting, but because I want to make sure I talk about it with the sensitivity and respect that the people who suffered here deserve.

Instead, I want to talk about how it felt.

I remember standing in front of the prison cells—some no larger than a cabinet—where people were kept standing for days as punishment for something as simple as stealing extra food. I was speechless. How could this be real?

In the courtyard where prisoners were forced to line up for hours to be counted, both morning and night, I felt a chill run down my spine.

And in the gas chambers—seeing the scratch marks on the stone walls and looking up through the hole in the ceiling where the gas had been released—I felt frozen. I stood there, overcome with sadness, anger, and utter confusion. How could people do this to other people? There are no words that can fully capture that feeling.

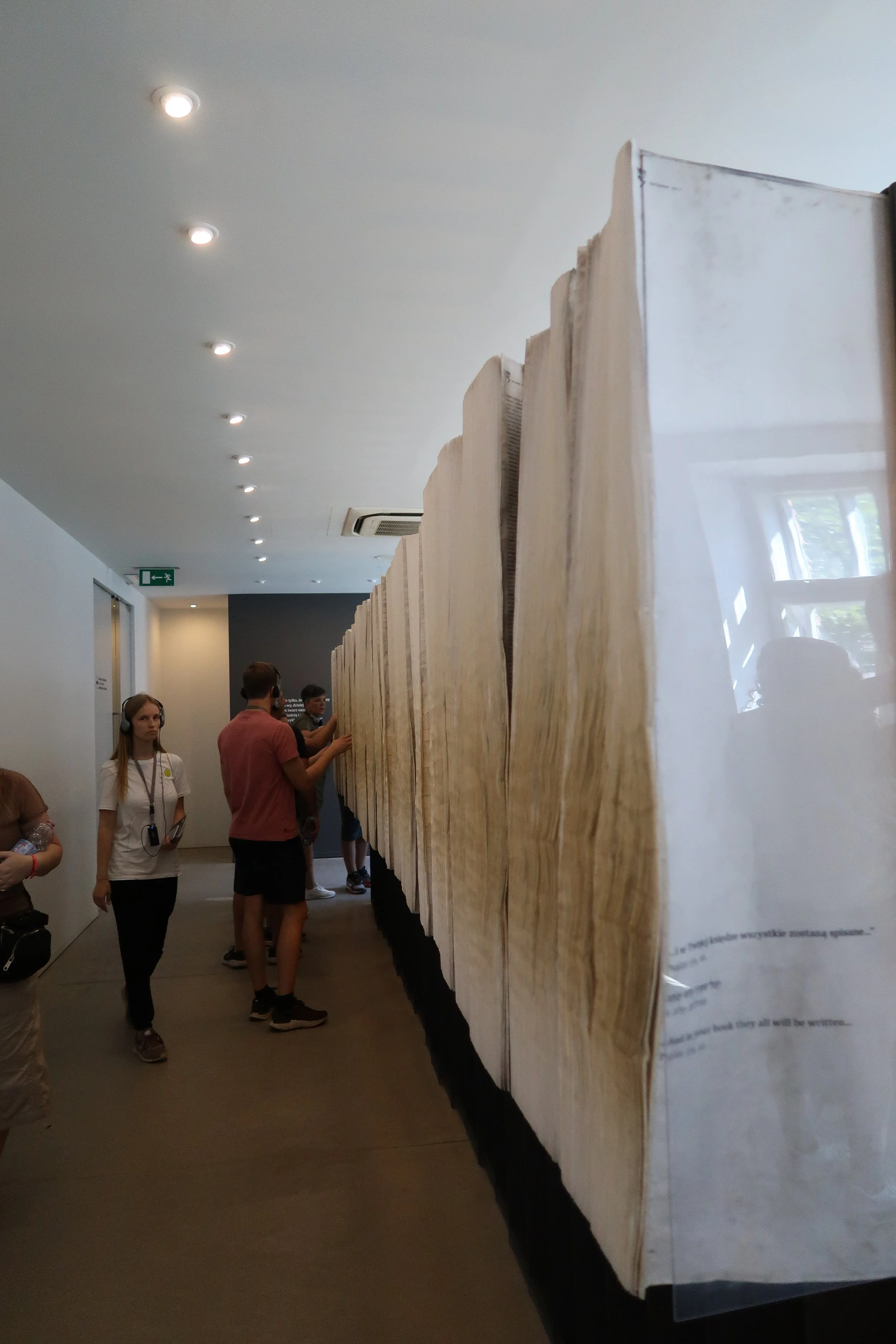

Walking through the museum memorial was another moment that hit me hard. We saw piles of items the Nazis took from arriving prisoners—pots, pans, glasses, suitcases, clothing, even human hair. But what shattered me was seeing the tiny shoes of a child who had no idea what their fate would be. That was the moment I finally broke down and cried.

Until then, I’d been in a state of shock—unable to fully process what I was seeing. But looking at those shoes gave me a deeper sense of perspective. It highlighted the sheer number of people—men, women, and children—who had been stolen from the world. Seeing the mountains of suitcases, prosthetics, and personal belongings was overwhelming. It was a visual reminder of how many lives were lost.

In the crematorium, my thoughts kept drifting to the children—how confused and scared they must have been. And the adults, too, who were gaining a sense of what was happening but had no way to stop it.

We then traveled to Birkenau, where the enormity of it all became even more apparent. Pulling up to the train tracks—the ones we’ve all seen in photos—felt surreal. These were the same tracks that brought cattle cars filled with Jewish families and others deemed "undesirable" by the Nazis.

We walked the same path that prisoners had walked when they arrived—through the selection process, where they were separated from their loved ones and judged on whether they were strong enough to work or sent directly to the gas chambers.

It was an unbearably hot day, and I couldn’t stop thinking about how the prisoners had to endure this same heat—without water, proper clothing, or shelter.

Walking through the barracks at Birkenau was deeply unsettling. Unlike Auschwitz, where we observed much of the camp from behind glass, at Birkenau we actually stepped inside. The barracks were haunting—completely silent. There was a heavy presence, almost like the walls still held the memories of the people who had lived and died there.

Looking at the rows of wooden planks that passed as beds, it was hard to imagine how anyone could have survived those conditions.

One thing I noticed in both camps: there were no flowers, no birds, and no sounds. Just a stillness that felt both calm and unbearably heavy.

Visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau was one of the most difficult and emotional experiences I’ve ever had. It’s hard to put into words the heaviness that comes with standing in a place where so much pain and loss occurred. But as hard as it was, I’m grateful I went. Bearing witness, learning, and remembering is the least we can do to honor those who suffered.

That said, our time in Poland wasn’t defined solely by the heaviness of that day. Kraków is a city overflowing with history, culture, and life. Walking its cobblestone streets, learning about its deep roots, and exploring everything from medieval castles to bustling markets reminded me of how much there is to discover in the world. This trip, though emotional at times, was also filled with curiosity, laughter, and a deeper appreciation for history—both its beautiful and heartbreaking parts.

Traveling through Poland taught me so much, and it’s a place I’m incredibly grateful to have experienced. It reminded me that while history holds dark moments, it also carries resilience, strength, and stories that deserve to be remembered. And that’s exactly why we travel—to connect, to learn, and to never forget.